10

April 2003

![]()

1. "Atop Mountain, Rebel Kurds Cling to Radical Dream", Joseph Logan reports from his visit to the Kurdish military camps in the Quandil Mountains in Iraq.

2. "KADEK: Democratic participation is necessary", KADEK’s Presidential Council member Gulizar Tural stated that Kurds needed democracy, not a puppet state. Tural emphasized that Turkey was in a cross and must review its relations with Kurds.

3. "Turkey, Iran both seek friendship in uncertain times", as American-led troops take control in Iraq, the Turkish government that declined to host them is pursuing alliances elsewhere in the region. Iranian foreign minister Kamal Kharrazi paid a sudden visit to Turkey on April 6, following US Secretary of State Colin Powell by four days. Citing "common interests" and "legitimate concerns" with its secular neighbor, Kharrazi met with Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erodgan and Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul. The visit left some observers wondering how friendly Turkey intends to become with neighboring Islamic regimes – and how conciliatory it wishes to be toward the United States.

4. "Turkey rules out permanent Kurd control of Kirkuk", Turkey said it would be unacceptable for Kurdish "peshmerga" fighters who swept into the northern Iraqi oil city of Kirkuk on Thursday to set up a permanent presence there.

5. "Turks living near Iraqi border uneasy at prospect of free Kurds", the prospect of Saddam Hussein's end sparks unease along Turkey's 218-mile border with Iraq, a region just recovering from a 15-year civil war that left more than 30,000 dead.

6. "Turkish cave-dwellers fear danger from Ankara, not Iraq", the Iraqi border lies only 100 kilometers (60 miles) away, but the troglodytes of Hasankeyf, in south-eastern Anatolia, do not fear war: what frightens them is a controversial dam that would drown their age-old cave dwellings.

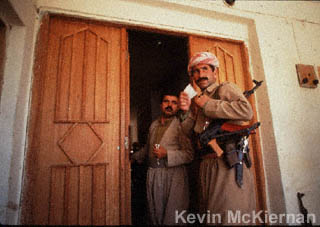

1. - Reuters - "Atop Mountain, Rebel Kurds Cling to Radical Dream":

IN THE QANDIL MOUNTAINS - Iraq / 9 April 2003 / by

Joseph Logan

Years ago, Teimour set out to bring revolutionary change to the

whole world, starting with the liberation of Turkey's Kurdish southeast.

Now, their guns fallen silent, he and other veterans of the war for autonomy for Turkey's Kurds make do with their own new society, splendidly isolated in the mountains of north Iraq. The rest of mankind will be just as free, they believe, eventually.

"Many things we want to achieve -- the equality of men and women, a just kind of labor -- exist here," Teimour said, speaking from one of a string of military camps that KADEK -- the group representing Turkey's Kurdish separatist movement -- has in the snowy peaks of Kurdish-held northern Iraq.

"It is far from complete, but it is a beginning."

To outsiders, it may look more like an end: the thousands of fighters the group says are spread through its rocky stronghold are the remains of the Marxist Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which launched a campaign for Kurdish self-rule in 1984.

Their battle with Turkish forces claimed more than 30,000 lives, led to martial law in southeastern Turkey and the destruction of thousands of Kurdish villages before Turkey abducted PKK head Abdullah Ocalan and sentenced him to die in 1999.

In captivity, Ocalan called on his fighters to lay down their arms and work for broader cultural and political rights. They heeded, fighting largely stopped and the PKK renamed itself KADEK in 2002, saying its armed struggle was on hold pending progress on the political front.

It has come -- Turkey eased bans on Kurdish broadcasting and education last year to help its bid to join the European Union -- but independently of the people once synonymous with Turkey's Kurdish question, now fighters without a war.

Osman Ocalan, Abdullah's brother and a senior figure in both the PKK and KADEK, insists the rebels remain a force in politics and, if they are attacked by Turkey or anyone else, on the battlefield.

"The PKK was never as strong politically or militarily (as KADEK). The number of guerrillas is more than the PKK had, and the political cadre is twice as big," he told a visitor, over a dinner of roasted chicken and foraged greens in a stone hut at one camp.

Flipping through channels on a satellite TV hook-up to settle on the group's Europe-based outlet, he conceded, however, that Turkey's capture of its arch-foe has cost the fighters a leader, while the turn to politics has blurred their focus.

"The only weak point is morale. The arrest of our president has shaken everyone very badly, and it has taken the past four years to get on our feet."

For leaders, the new realities lead to strange places: Osman suggests a U.S.-Turkish rift over war in Iraq may be a political windfall, and says he seeks dialogue with Washington, which considered the PKK terrorists and views KADEK the same way.

"They need the Kurds," he explained to a visitor, as the men and women on guard duty milled nervously about their leader. Pointing to U.S. military cooperation with Iraqi Kurds, he said the Kurds are poised for a role in regional politics.

"If the Americans miss this chance, they will squander politically whatever they have won in the war."

For the rank and file, the period of limbo in the mountains has become a sort of monastic retreat, during which they can devote themselves to the principles that led recruits, many of them foreigners, to join the PKK's campaign in Turkey.

A lanky, bespectacled German who identified himself as Mardoum -- his Kurdish nom de guerre -- has been here for about three years, having joined the PKK around the time Turkish commandos dealt it a body blow by kidnapping Abdullah Ocalan.

"When I became concerned with the Kurdish issue and thought seriously about joining, what settled it for me was the social dimension, the fact that Turkey and Kurds are really just an element of the larger question," he said.

"Here, it is easier perhaps to concentrate, to devote yourself to the fight without being caught up in things that have nothing to do with revolution."

Others echo the sentiment that they are cultivating the habit of revolutionary virtue through everyday life.

Teimour, a veteran of the PKK's days of residence in Lebanon fondly welcomes a visitor from Beirut, whom he is eager to show the vegetable garden his comrades are weeding outside one of the group's checkpoints, under the gaze of a hostile watchdog.

"It's going to be beautiful; all these vegetables from right here," he beamed. "Go have a look, but be careful of the dog."

About a third of the group's members of women, who seem to do much of the armed duty day in and day out, while many of their male colleagues cook and clear the dishes after meals.

"We have no illusions about who should be doing what, partly because we cannot afford to have them," said a woman who directs one of the groups of female fighters. "Out of necessity, every one of us is a baker, a carpenter, a cook."

They are hundreds of miles removed from the places they hope to see liberated, but the distance, said a fighter called Firat, seems less.

"As a matter of pure geography, yes, of course we are cut off from northern Kurdistan," he said, referring to the largely Kurdish areas of southeastern Turkey. "But what we are doing here is intimately connected with the struggle there."

In any case, said a member who identified himself as Hebun and has not seen his home town of Diyarbakir -- the center of Turkey's Kurdish area -- since 1994, it is harder to long for a place you know not to be free.

"I miss it, at times," he admitted. "But

one realizes that it cannot be your home so long as this system that

conspires against human beings exists and is in place." ![]()

2. - Kurdish Observer - "KADEK: Democratic participation is necessary":

KADEK’s Presidential Council member Gulizar Tural stated that Kurds needed democracy, not a puppet state. Tural emphasized that Turkey was in a cross and must review its relations with Kurds.

MHA/FRANKFURT / 8 April 2003

Participated by telephone in the “Acilim” program on Medya

TV the other day, KADEK Presidential Council member Tural stated that

the Middle East had been intervened militarily as it could realize its

renaissance. Calling attention that the existing incidents had positive

developments as well as big dangers, Tural said that restructure would

only be possible by will power of the peoples living there. The council

member pointed out that the existing solution did not give them any

chance for democracy and their own will that were their real needs and

continued to say the following: “There are important lessons drawn

from the past experiences. If Kurds use them they can be an important

dynamic force for the transformation of the region.”

Common stance

Tural called on the Kurdish people to display their common stance and willpower to participate democratically. “We as the Kurdish people need democracy more than bread and water,” said Tural. “It is a critical process and has its dangers. There is a risk that Kurds might be used against their own people, to participate in massacres. No Kurd must ever be used.”

Relations of vital importance

The council member underscored that relations between Kurds must be considered the relations of vital importance and said the following: “Restructure is a main point that we must take into consideration as far as the resolution to the Kurdish question is concerned. If it includes a democratic federation, freedom and equality it must be discussed. The region has entered into an extremely important phase. The policies of destruction and denial, the existing status quo will be abandoned. Even new changes in the geography might come into the agenda.”

Tural also stressed that the Kurdish people preferred a democratic solution.

“Turkey has two alternatives”

Gulizar Tural stated that Turkey must examine its approach to Kurds in order to be effective in South Kurdistan. “Turkey has two alternatives. Either it says, our policy about Kurds must change, or it consents to reduce the region into the statue of colony.”

The council member emphasized that the same was valid for Syria and Iran too and that the problems could be solved by re-examining the relations with Kurds.

Tural continued with words to the effect: “Kurds

cannot ever be together with forces that move with the 20. century status

quo. But peoples who cannot change it cannot unite with forces that

do not accept their democratic unity. It is obvious from the examples

in history. Kurds must be insistent on their democratic solution. They

must establish their organizations, to establish peace in the region.”

![]()

3. - Eurasianet - "Turkey, Iran both seek friendship in uncertain times":

9 April 2003 / by Mevlut Katik *

As American-led troops take control in Iraq, the Turkish government

that declined to host them is pursuing alliances elsewhere in the region.

Iranian foreign minister Kamal Kharrazi paid a sudden visit to Turkey

on April 6, following US Secretary of State Colin Powell by four days.

Citing "common interests" and "legitimate concerns"

with its secular neighbor, Kharrazi met with Prime Minister Recep Tayyip

Erodgan and Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul. The visit left some observers

wondering how friendly Turkey intends to become with neighboring Islamic

regimes – and how conciliatory it wishes to be toward the United

States.

While it is unclear how meaningfully Powell’s visit affected Kharrazi’s timing, mutual insecurities probably spurred both sides. Concerns about upheaval and disintegrating borders are also apparently prodding Erdogan’s government toward conversations with a range of regional players – some of whom, like Iran, lie explicitly out of Washington’s favor. "The riches of the region are being wasted. From that viewpoint, it is very natural and right to hold consultations and to exchange views," Gul told a press conference on April 7. "We have held bilateral talks with Iran within this framework. Naturally, we will be holding talks with Syria. It will be very beneficial to hold bilateral talks with the other neighboring countries. These activities will continue."

Gul announced that he would fly to Damascus on April 13 to have talks with Syrian leaders. Turkey, however, is playing its diplomacy with delicacy. It declined Kharrazi’s offer to set up a tripartite consultation mechanism among Ankara, Damascus and Tehran, an analogue to which operated briefly after the first Gulf War.

In the immediate term, Turkey and Iran both see more to fear than to exploit in an unstable Iraq. Ankara and Tehran worry about the possibility that ethnic Kurdish communities in their respective countries could stage insurgencies if their fellow Kurds become aggressive in a post-Saddam Iraq. Both countries may fear that ethnic claims on land in Iraq, or insurgencies by the Kurds of northern Iraq, could fuel separatist movements elsewhere in the region. Kharrazi said in Ankara that "Iran, like Turkey, favored Iraq’s continued territorial integrity." While Iran does not countenance Turkey’s retaining the right to enter northern Iraq if it perceives a threat from Kurds, the two countries appear more concerned about preserving their own borders than gaining advantage over the other.

The talks also seem parallel to one of Erdogan’s major goals, which involves hastening Turkey’s entry into the European Union. German Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer and British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw are expected to visit Turkey in the coming weeks, while Polish Prime Minister Lezcek Miller visited Erdogan on April 7. Miller announced that Poland would dispatch 50 chemical and biological warfare experts to Turkey under the auspices of NATO, which has set up a program for Turkish defense. Miller, however, reportedly took the occasion to assert his country’s support for Turkey’s application to the European Union. Gul and Erdogan left the next day for Belgrade to attend a conference of parties to the Southeast European Cooperation Process, which first met in 2001.

Erdogan’s boldest initiative may be his effort to hitch his Justice and Development Party (AKP), with its Islamist roots, to Iran and other Islamic countries, particularly in trade. Turkish exports to Iran were basically flat in January 2003 compared to the same period in 2002, and exports to other Islamic countries had fallen. Since Erdogan has stated a desire to increase trade with neighbors and other Islamic countries by 50 percent, some of his government’s openness may serve as a means to boost his country’s weak export revenue. [For background, see the Eurasia Insight archive].

This initiative risks irritating the United States without any guarantee of easy progress in the target countries. Tehran opposes any Turkish military intervention in northern Iraq, and Gul noted this opposition with Kharrazi. But Turkey continues to say that it will send soldiers across the border if it faces a flood of refugees or if Kurds try to seize Turkish oil assets. Kharrazi implicitly reminded the Turks that Tehran could claim grounds for doing the same. "There are not only Turkmen in northern Iraq, but also Shiites," with whom Iran has religious sectoral ties, he said in Ankara.

Moreover, Ankara and Tehran compete over ways to export Caspian energy – so acutely that Erdogan, during a press conference with Polish Prime Minister Miller, reportedly made an inaccurate reference to "Caspian oilfields" as an area Turkish troops would protect from Kurds – and worries that Iran may purchase Iraqi oil rather than natural resources from Turkish sources.

Despite some demarches and rhetoric about increased cooperation between Ankara and Tehran, a smooth road to partnership is unlikely. And if Turkey’s diplomatic dealings are sensitive with Iran, they will be more sensitive with Syria and other Middle East nations. Meanwhile, the country’s effort to join the European Union, which would give it deeper reserves of security and economic opportunity, may proceed more quickly than any ties with the Islamic world. Turkey’s rapprochement with Iran will probably cleave for the time being to economic issues and certain elements of Kurdish policy. But the changes sweeping across Iraq may complicate even these areas of agreement.

* Editor’s Note: Mevlut Katik is a London-based journalist

and analyst. He is a former BBC correspondent and also worked for The

Economist group. ![]()

4. - Reuters - "Turkey rules out permanent Kurd control of Kirkuk":

ANKARA / 10 April 2003

Turkey said it would be unacceptable for Kurdish "peshmerga"

fighters who swept into the northern Iraqi oil city of Kirkuk on Thursday

to set up a permanent presence there.

"It wouldn't be important if the Kurdish peshmergas were acting spontaneously and withdrew. But it would be unacceptable if they were there permanently," a senior foreign ministry official told reporters as Kurdish and U.S. forces poured into the city after Iraqi forces gave up defending it.

Turkey fears that Iraqi Kurds could use control of Kirkuk to provide the financial basis for an independent state. The Kurds and their U.S. allies say a bid for independence is out of the question.

Turkey has a large armoured force near the Iraqi border and says it could enter Iraq if its interests were threatened. It fears an independent Kurdish state in northern Iraq could lead to similar demands by separatist Kurds in southeast Turkey.

Foreign Minister Abdullah Gul said earlier that Turkey was watching events in northern Iraq closely.

The United States has offered Turkey $1 billion in aid and stressed that Turkish armed forces should not enter northern Iraq as this would antagonise Iraqi Kurds and destabilise the situation.

"Everything is being followed very closely," Gul told reporters at the foreign ministry. "Whatever is necessary will be done. Talks are being carried out. Turkey's stance on this issue is clear and open."

Kurdish commanders in northern Iraq told Reuters that Kirkuk, at the heart of Iraq's oil industry in the north, was "under control". Reuters reporters on the city's outskirts saw hundreds of Kurdish guerrillas enter the city.

Both Iraqi Kurdish leaders and the United States say the

formation of a breakaway Kurdish state is out of the question but Turkey,

still smarting from more than a decade of conflict with its own separatist

Kurdish rebels, has its doubts. ![]()

5. - The State - "Turks living near Iraqi border uneasy at prospect of free Kurds":

CIZRE / 10 April 2003 / by Kevin G. Hall

The prospect of Saddam Hussein's end sparks unease along Turkey's

218-mile border with Iraq, a region just recovering from a 15-year civil

war that left more than 30,000 dead.

Ethnic Kurds are a majority in this southeastern corner of Turkey. A state of emergency imposed on their region by the government in Ankara in 1987 was lifted just last November, and Kurds still cannot learn their language in public schools or even watch television in their tongue.

Now the war in Iraq is stoking the coals of Turkey's long-standing ethnic conflict with the Kurds. The Turkish military has warned repeatedly that it would invade to quash any effort to establish a Kurdish state in northern Iraq. Kurds fear the Turks would use any unrest in the region as a pretext to intervene and oppress Kurdish Turks, whom they mistrust.

"Turks look at this place as a ticking time bomb," said Ersel Aydinli, a political scientist at Bilkent University outside the Turkish capital.

Kurds contend that the Turkish military is training paramilitary squads made up of 1,500 ethnic Kurds to operate in northern Iraq once Saddam's government falls. The forces reportedly are being trained on military bases in and around Cizre, near the border with Iraq, where Muslims believe Old Testament figure Noah is buried in a 15-foot tomb.

Talk of paramilitary forces, or death squads, is difficult to confirm or deny in a region dominated by rumor and fear - and a military that never talks about its actions. Since the 1980s the Turkish military has openly armed and trained on its bases the Kurdish "village guards," who fought separatists seeking an independent state called Kurdistan.

Human rights groups accuse some of the 90,000 village guards of operating death squads, and abuses committed by the guards and the military in the southeast were highlighted in the State Department's annual Human Rights Report released March 31.

Human Rights Watch on March 26 issued a statement calling on Turkey to "not deploy to northern Iraq any paramilitary groups" like those responsible for killings and disappearances in the 1990s. It voiced concern about the Lightening Group, a squad of guards reportedly being trained now.

"Turkey has a bad record of violations against civilians while battling rebel Kurds in southeast Turkey," Elizabeth Andersen, the group's executive director for Central Asia, said in a statement March 26. "It needs to be taking precautionary steps today, to make sure its troops don't commit repeat violations in any operations it undertakes in northern Iraq."

When Secretary of State Colin Powell visited Turkey on April 1, he tried to calm Turkish concerns by saying the United States does not support an independent state for Kurds, who live in parts of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey. In exchange, he was assured that Turkish troops would not be sent into northern Iraq unless Turkey's security was clearly threatened.

Local Kurds fear that paramilitary forces will be doing the bidding of the Turkish military instead.

"The United States will let Turkey enter into northern Iraq with paramilitary forces," said Mustafa Karahan, head of the Diyarbakir office of the Democratic People's Party, known by its acronym Dehap. Diyarbakir is the largest Kurdish city in the southeast, and Dehap is Turkey's largest Kurdish political party. Kurds make up about 20 percent of Turkey's population of 68 million.

Turkey's powerful military does not discuss its operations and keeps much of southeastern Turkey in a near-lockdown state.

"Report only what you see," cautioned a soldier at one of numerous military checkpoints. To assist in war coverage, Turkey has established press centers in southeastern cities, and foreign journalists are told they are free to roam the southeast.

Their freedom is limited, however. Reporters cannot get near many bases or the nine-mile buffer zone north of the Iraqi border established in 1997. Turkey keeps at least 5,000 men posted along the buffer zone. A British Broadcasting Corp. reporter was kicked out of Turkey this month for airing video obtained from restricted areas. Reporters have been turned back for seeking access to villages destroyed in the 1990s or other remote areas.

Secret police and informants are another problem, Kurds say. One Kurd in Cizre, who asked not to be identified, told of kinsmen paid $1,000 and sent last month into Iraq to report on Kurdish separatists there.

The man suggested reporters look for village guards in the nearby Cudi neighborhood.

Locals there are clearly unhappy with questions about village guards. One well-dressed man who clearly carried authority and shooed away onlookers said grimly, "You shouldn't ask those questions here."

The village guards, he said, were "off on operations."

He suggested the reporters leave.

On the way out, a man in a suit appeared, unusual for an area that is in some places knee-deep in mud. He approached the translator and said, "I heard you were asking questions about village guards. Did anyone point you to one? Did anybody give you a name?"

Perhaps the man was with the secret police or an informant. Perhaps he was a henchman for chieftains called Aga (pronounced Aah), who control the smuggling of drugs, arms and people across the Iraqi border.

There was nothing ambiguous about his final question,

however: "Are you leaving now?" ![]()

6. - AFP - "Turkish cave-dwellers fear danger

from Ankara, not Iraq":

HASANKEYF / 10 April 2003 / by Pierre-Henry Deshayes

The Iraqi border lies only 100 kilometers (60 miles) away, but the

troglodytes of Hasankeyf, in south-eastern Anatolia, do not fear war:

what frightens them is a controversial dam that would drown their age-old

cave dwellings.

The ancient city of Hasankeyf, once a jewel of Mesopotamia, has survived conquest from Byzantium, the Arabs and Ottomans, only to face flooding from the Tigris river waters -- its long-time lifeblood. A thousand years ago, Hasankeyf could boast a population of 15,000 - two and a half times that of Constantinople (now Istanbul), the capital of Byzantium.

But today only 4,000 still live in Hasankeyf. Many chose

to leave rather than risk losing all their belongings to flooding. Nearly

50 years ago, the Turkish government embarked on a massive regional

development scheme, the South-east Anatolia Project (GAP), which included

22 dams and 19 hydro-electric power stations on the Tigris and Euphrates

rivers.

Several dams were built but the controversial Ilisu Dam, which threatens to engulf Hasankeyf, is still at planning stage. Ilisu would also flood hundreds of other archaeological sites and deprive 30,000 people in this mainly Kurdish region of their homelands.

In 1972 the government asked the people of Hasankeyf to leave their caves, dug out by their forebears nearly 10,000 years ago, and move into a new town built nearby. But in recent years Ankara has become more sensitive to historical and cultural considerations - especially since fighting between the Turkish army and Kurdish separatists halted in 1999, attracting increasing numbers of tourists to the region. At the same time, public or private financial backing for building Ilisu has grown scarce under pressure from environmentalists and human rights campaigners.

"I'm fed up with this uncertainty. Either they build the dam and we move out, or they give up the idea and we can start making plans for the future. Right now, we have no idea of what is going to happen," says Hasan, whose family of destitute cattle breeders is one of the few to still inhabit a cave. The family's washing dries in the sunshine outside the cave, near the top of a hill overhanging the Tigris' deceptively calm waters, not far from a 13th-century ruined citadel.

The cave has enjoyed electricity for five years now, but no pipes were ever laid to bring up water, which is carried uphill by donkeys. Unusually in this part of the world, Hasan, at 25, is still single: he's too poor to find a bride. "The government has asked us twice to move into the (new) town but we can't afford a house," he says. "Of course if they gave us one, we'd leave this place with no regrets."

"We're of two minds: we too want the dam, in order

to promote regional development, but we don't want to open a new chapter

in our entire history," said a local municipal worker. Unsurprisingly

then, for the people of Haysankayf, concern over their own fate takes

precedence over the war in Iraq. ![]()