21

February 2003

![]()

1. "It's been 3 months!", KADEK President Abdullah Ocalan who was being kept in a solitary cell in Special Type Prison in Imrali was not allowed to see his lawyers and family members on the pretext of "bad weather conditions". Thus the ban on visit entered into its 12. week.

2. "The Turkish military and northern Iraq", by Dr Robert M Cutler, Institute of European and Russian Studies, Carleton University, Canada

3. "Turkish military calls for new emergency rule", Turkey's powerful armed forces have urged the government to reimpose emergency rule in the south-east of the country in the event of a US-led war against neighbouring Iraq.

4. "Turkey plays ancient game", Turkish carpet vendors are famous bargainers, and more than a few Americans have been persuaded to part with wads of cash in their shops in Istanbul. But nothing in Turkish-American history has approached the great haggle over an impending war with Iraq.

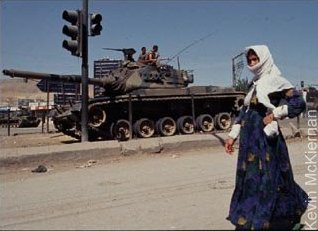

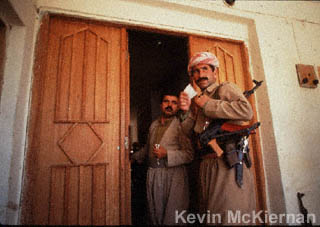

5. "Turkey Assesses Question of Kurds", as Turkish and American diplomats struggled this week to strike a deal on the use of American troops in northern Iraq, one of the most intractable hurdles for negotiators has proven to be Turkey's bitter history with the Kurds.

6. "Turkey's leader blames EU for failing to give political support in crisis", Turkey's de facto leader, Tayyip Erdogan, yesterday lashed out at Europe for failing to provide it with the necessary political support to confront the crisis over Iraq.

7. "Flashback for the Kurds", as the Bush administration struggles to induce Turkey to support a war with Iraq, our Kurdish allies in northern Iraq are realizing that once again America is about to double-cross them.

8. "A film puts faces on unseen street children in Turkey", by Ilene R. Prusher.

1. - The Kurdish Observer - "It's been 3 months!":

KADEK President Abdullah Ocalan who was being kept in a solitary cell in Special Type Prison in Imrali was not allowed to see his lawyers and family members on the pretext of "bad weather conditions". Thus the ban on visit entered into its 12. week.

BURSA / 20 February 2003 / by Bayram Aslan

Ocalan's sisters Havva Keser and Fatma Ocalan and his brother Mehmet

Ocalan went to Gemlik together with lawyers Tim Otty, Aysel Tugluk and

Bekir Kaya and as interpreter journalist-writer Ragip Duran. Made wait

at Gemlik Gendarme Station for nearly two hours, the visitors were informed

that they could not go to the island on the pretext of "bad weather

conditions".

Chief Prosecutor: Officials do not allow it

After the fiasco the lawyers and family members went to Bursa. While his sisters waited outside, the lawyers and brother Ocalan met with Deputy Chief Prosecutor Cemil Kuyu. Then the group also met with Chief Prosecutor Emin Ozler. Two hours later Tim Otty, Ocalan's English lawyer representing him at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), talked to the correspondents. Otty said that they had come to Gemlik in order to visit their clients but after waiting two hours they had not been allowed to see him due to "bad weather conditions". The lawyer stated that the situation was extremely worrying, adding the following: "It cannot continue as such. I shall inform ECHR, Ministry of Justice and the European Committee for Preventing Torture (CPT)." Otty stressed that though they had requested to go to the island by a helicopter, it was turned down without a justification and said that he would stay until Friday in case there might be a visit and if not he would return to London.

Tugluk: The meeting passed in tension

And lawyer Aysel Tugluk gave information on the meeting

with the Chief Public Prosecutor. Tugluk said the following: "Mr

Otty requested a helicopter. But the prosecutor stated that the Justice

Ministry did not have any helicopters. Then Mr Otty reminded that the

CPT delegation was assigned a helicopter, but the prosecutor claimed

that the CPT delegation worked with ECHR and the agreement was binding

for Turkey, and they were officials whereas we were private. Our English

associate argued that they too did a public service, and though they

had suggested that a helicopter or a suitable vehicle should be assigned

but they were not even replied. Mr Otty asked, 'Why is the visit only

on Wednesday? There must be visits at the other days of the week. The

boat "Imrali-10" or a security boat should be assigned for

us' and listed his demands. The prosecutor said that the officials did

not give permission for visit on another day. But Mr Otty insisted on

necessary steps to be taken as soon as possible and said that he would

take the matter to ECPR and CPT." Tugluk pointed out that the meeting

passed in tension and the prosecutor replied insisting questions with

some reaction. ![]()

2. - The Asia Times - "The Turkish military and northern Iraq":

20 February 2003 / by Robert M Cutler *

Press reports have indicated that what separates the United States

and Turkey in their negotiations is the size and nature of the economic

package wanted by Ankara. This is partly true, but it is not the whole

story, and not even necessarily the most important part of the story.

Military aspects of any Turkish incursion into northern Iraq and political

aspects of northern Iraq's future are, rather, the more significant

sticking points. Before discussing the latter, it is nevertheless useful

background to review how the level of the economic package has recently

increased.

Ten days ago the first press reports appearing in American sources mentioned a size of US$15 billion for the economic package. This figure increased to $20 billion before Turkish politicians declared even this insufficient on the weekend and postponed the planned February 18 parliamentary vote on the presence of American soldiers on Turkish soil to prepare for the invasion of northern Iraq. Following intensive negotiations by the two sides at the highest levels, the figure next quoted in the press was $26 billion. This number was qualified as the final American offer.

But even agreement on a number would not be enough to seal a deal, for the composition of the package is also disputed. The US is offering direct grants of about $6 billion, with the remainder composed of loans and trade concessions. However, Western diplomats in Ankara are quoted as saying that Turkey is seeking $10 billion in grants, $15 billion in credits and loans, and nearly $7 billion more in forgiveness of military debts. (Reported figures that approach $50 billion probably include the value of Turkish participation in postwar reconstruction projects in Iraq.) The subtext of statements by Turkish government leaders indicates that Ankara may not consider the deal sealed until it is voted by the US Congress, which must approve it for the agreement to be legally binding on the executive branch. But settling the economic package may be the easy part.

Likewise 10 days ago, there were reports of a tacit US-Turkish-Kurdish agreement that would permit between 10,000 and 20,000 Turkish troops to enter northern Iraq, ostensibly to secure a strip of Iraqi territory shadowing the border, so preventing (nonexistent) Kurdish pretensions to political independence in northern Iraq from bearing fruit. In fact, the purpose of this deployment would have been to hunt down armed PKK remnants that withdrew into northern Iraq when the PKK dissolved itself in the late 1990s and then re-formed itself as KADEK, focusing on social action in Turkey rather than armed struggle.

According to that tacit agreement, American troops would march on Mosul and Kirkuk, and Turkish and Kurdish elements would agree not to attempt to enter the cities, while the Turks would reserve the right to do so if the Kurds did. This agreement was indeed so tacit that a three-way meeting presided over in Turkey by Zalmay Khalilzad, President George W Bush's special envoy to the Iraqi opposition, broke up without manifest agreement, and with the Americans reduced to warning both other parties simply to stay away from the two cities concerned. Relations between the Turkish authorities and the Iraqi Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) have progressively worsened since then, while Washington's positive rapport with the KDP has created a bone of conflict with Ankara.

The first figure circulated in reports - of 10,000 to 20,000 Turkish troops in northern Iraq - became inflated to 38,000 in later reports last week. This is about the same as the number of American soldiers projected to occupy northern Iraq. Thirty-eight thousand Turkish soldiers would be enough to restrict severely, if not eliminate, the autonomy of action of the Iraqi-Kurdish KDP headquarters in Irbil. As the economic deal faltered, press reports in Turkey alluded to plans by the country's military general staff to put in fact twice that number of Turkish soldiers - a full 76,000 - into northern Iraq, from where they would march literally halfway to Baghdad.

This number of Turkish troops could exert significant political and strategic pressure on all the major cities in the KDP canton: not only Irbil (as well as Dohuk) but also the area around Mosul - the nominal capital of Iraqi Kurdistan under the joint KDP-PUK regime in the 1990s - not to mention a major segment of the pipeline taking oil from Kirkuk to Turkey's port at Ceyhan. And still the dimension and extent of Turkey's military deployment in northern Iraq is not the last sticking point.

The Turkish press has in the past few days given acute voice to the indignation felt by Turkish military staff over apparent American insistence, or perhaps naive assumptions, that Turkish troops in northern Iraq would be under US command. Perhaps in response to this, hints were made as recently as Tuesday in Ankara that Turkish troops could enter northern Iraq with their own battle plan and their own military objectives. Part of this misunderstanding between the two sides may have been an initial American assumption that the US-Turkish campaign in northern Iraq would have a NATO aegis, creating the possibility for American command leadership of Turkish troops. But the Turks were not pleased by this assumption, which outlived NATO unity over military assistance to Turkey.

As of late Tuesday, Andalou Press Agency reported that the US and Turkey had "made progress in political aspects of negotiations and they partially reached an agreement on [the] 'command' issue". This may involve allowing Turkish troops a privileged place in Kirkuk, where Ankara claims special concern with the Turkmen in the city, or even Mosul itself, but more probably Irbil. (Irbil and Kirkuk are by population the two major Turkmen cities in Iraq.) This was not to be a reversal of the original Turkish-Kurdish understanding over the mutual non-intervention agreement, brokered by the US but which fell apart at the meeting presided by Khalilzad. That is because Kirkuk would be in the canton of northern Iraq controlled by the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which - in contrast with the KDP - has had very good relations with Turkey ever since dropping support for the PKK some years back.

And yet the final outcome is still undetermined. American troop ships will arrive in the region before too long, and they will have to know by then where to go when they get there. The Pentagon has an undivulged date by which they must know whether Turkey is available as a staging-area/launching-pad, and on which date they will have to begin implementing backup plans if it is unavailable: which still would not mean that Turkey would not intervene unilaterally in northern Iraq. Even if some sort of joint US-Turkish command were established - which is far from being certain - nothing prevents the Turkish military from pursuing its own objectives in northern Iraq. Indeed, this is to be expected and has regularly been declared by both military and political leaders in Ankara. It may be expected, further, that regardless of any cooperation between the two sides, actual Turkish war goals in Iraq will be made no more transparent to the Americans, than the Americans have made their own war planning to the Turks.

It remains to be seen at what point the national interests of Turkey and the United States may diverge in practice, not only tactically on the ground but also strategically in the political aftermath of the war. The first evident conflict regarding the latter will come when the Turks will push for the Iraqi Turkmen to be given a prominent role in a post-Saddam Iraqi government, whereas the Turkmen have been marginalized in the planning by Iraqi exiles and expatriates as well as by the American sponsors of the latter. That is when the military situation on the ground in northern Iraq after the end of hostilities will first show its political significance for Baghdad.

* Dr Robert M Cutler is Research Fellow, Institute

of European and Russian Studies, Carleton University, Canada, http://www.robertcutler.org

![]()

3 - The Financial Times - "Turkish military calls for new emergency rule":

ANKARA / 20 February 2003 / by Leyla Boulton

Turkey's powerful armed forces have urged the government to reimpose

emergency rule in the south-east of the country in the event of a US-led

war against neighbouring Iraq.

Although the proposal has been rejected by the reformist government, it demonstrates the domestic headaches Turkey could face in a war to topple Saddam Hussein, Iraqi leader.

The suggestion came as Ankara appeared to soften its stance in negotiations with Washington over financial rewards for allowing the US to deploy troops in Turkey for the opening of a second front against Baghdad. Colin Powell, US secretary of state, said the level of compensation on offer to Turkey was final but some "creativity" was possible. Ali Babacan, economy minister, said Turkey wanted written guarantees of the $24bn package.

In spite of an end-of-week US deadline for Turkey's answer, parliament on Thursday went into recess without voting on the US troop deployment.

General Yasar Buyukyanit, a military leader, proposed reintroducing emergency rule - with restricted individual rights and increased powers for the security forces - in six Kurdish-dominated provinces near the border with Iraq.

The request stems from the military's fear that Kurdish separatists, whose 16-year uprising in the south-east was all but crushed by the imprisonment of their leader, Abdullah Ocalan, would seek to take advantage of a war next door.

But reimposing emergency rule just months after it was lifted would cause an outcry in reformist circles at home and within the European Union, which has applauded sweeping human rights reforms adopted by the recently elected Justice and Development party.

Abdullah Gul, prime minister, has vowed that regardless of any war, the new government will not be deflected from moves to align Turkey with the EU'S criteria for starting membership talks.

But the military are still sufficiently influential - and public opinion is so bitter about Kurdish "terrorists" - that any provocation could be seized on to put pressure on the government to backtrack.

Osman Ozcelik, a member of the pro-Kurdish Hadep party, which dominates local government in the south-east, said the reimposition of emergency rule would undo the one tangible sign of liberalisation in the south-east and "reinforce people's lack of trust in the state".

The government is now preparing a new package of reforms

to meet EU human rights criteria, including measures to facilitate the

implementation of changes allowing Kurdish-language education and broadcasting.

![]()

4. - Globe and Mail Update (Canada) - "Turkey plays ancient game":

21 February 2003

Turkish carpet vendors are famous bargainers, and more than a few

Americans have been persuaded to part with wads of cash in their shops

in Istanbul. But nothing in Turkish-American history has approached

the great haggle over an impending war with Iraq.

Washington wants Turkey's permission to base troops there for an invasion of Iraq from the north, a second front to complement the assault from Kuwait in the south. Turkey seemed to say Yes earlier this month when its parliament voted to let the U.S. military modernize Turkish ports and bases to make them ready for the arriving Americans. Then, this week, the Turks stung their U.S. allies by delaying a second vote authorizing the U.S. deployment. That threw into doubt the whole U.S. military strategy for an Iraq war.

The immediate issue is money. In return for its welcome mat for U.S. troops, Turkey at first demanded a jaw-dropping $92-billion (U.S.). It has since brought its price down to about $30-billion, and Washington came back with $26-billion. That, say the Americans, is their final offer.

There the matter stands: a carpet-shop standoff. Washington says it doesn't really need Turkey's overpriced welcome mat, because it can stage its invasion in other ways. Donald Rumsfeld, the U.S. Defence Secretary, said the military has "work-arounds" in case Turkey is unavailable. It could parachute troops into northern Iraq or fly them in from ships.

The White House says it is not bluffing. It is "decision time for Turkey."

Turkey says it feels "no great pressure" to decide. It is an ancient game. As the customer walks theatrically toward the door, the carpet seller studies his fingernails.

The whole game strikes many in Washington as unseemly.

Turkey is, after all, a close ally and strategic partner of the United

States. Washington has backed Turkey's bid for membership in the European

Union and helped it weather an economic crisis. The Americans don't

like being fleeced in return. ![]()

5. - The New York Times - "Turkey Assesses Question of Kurds":

ISTANBUL / 21 February 2003 / by Dexter Filkins

As Turkish and American diplomats struggled this

week to strike a deal on the use of American troops in northern Iraq,

one of the most intractable hurdles for negotiators has proven to be

Turkey's bitter history with the Kurds.

The long struggle between the two groups, which resulted in one of the region's bloodiest insurgencies in the 1990's, is figuring prominently in Turkey's calculations over how to deal with the Bush administration's request to use the country as a base for thousands of combat troops.

In an interview tonight on Turkish television, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the leader of Turkey's governing party, said for the first time that the future of Iraq's Kurdish area, which abuts a border region of Turkey also heavily populated by Kurds, was weighing heavily on the negotiations.

"The case here is not as simple as bargaining over dollars," Mr. Erdogan said. "We're talking about the restructuring of the region. How the situation there is going to play out; we have to assess all of this."

Mr. Erdogan provided few details, but he hinted at what Turkish officials here have been saying privately for weeks: that if war comes to Iraq, the overriding Turkish objective would be less helping the Americans topple Saddam Hussein, but rather preventing the Kurds in Iraq from forming their own state.

For years, this vision has haunted Turkish officials, who fear that Kurdish autonomy in Iraq could revive similar dreams among the 12 million Kurds living in Turkey.

To make sure it does not happen, the Turks are planning to send thousands of their own troops into northern Iraq behind an advancing American army. The reason offered in public is to control the flow of Kurdish refugees, thousands of whom poured into Turkey following the Persian Gulf war in 1991.

Publicly, at least, the other two protagonists in the operation, the Americans and the Kurds, say they are willing to go along. In private, though, the Turkish plans appear to be causing deep unease among both the Americans and the Kurds, who fear that Turkey's aggressive designs threaten to ignite deep-seated ethnic feuds in the region, complicate America's own war plans and lay the groundwork for Turkey to dominate the Kurdish region in a post-Hussein Iraq.

The Turkish fear of Kurdish independence is so intense that some analysts here have put forward another possibility: if the Americans get bogged down fighting the Iraqi Army in the north, Turkish troops may try to seize the oil fields near Kirkuk and Mosul, to ensure that they stay out of Kurdish hands.

"The bottom line is that the Turks will do whatever they can to hinder the development of a Kurdish state in northern Iraq," said Mensur Akgun, director of foreign policy at the Turkish Social and Economic Studies Foundation. "If worse comes to worse, Turkey would be willing to occupy those areas, at least temporarily."

The roots of the modern Turkish-Kurdish feud lie in the territorial settlements that followed the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I. In drawing the boundaries of what became the modern Middle East, the victors left the Kurds without a country, and instead dispersed the Kurdish population among Iran, Syria, Turkey and Iraq.

The postwar settlement also denied Turkish claims to large parts of northern Iraq, which holds substantial populations of ethnic Turks.

While the Kurds long harbored dreams of their own state, those hopes, in the 1990's, crystallized into armed conflict. Under the leadership of Abdullah Ocalan, Kurdish rebels in Turkey mounted a violent bid for a separate state. It took the Turkish government most of the decade to crush the insurgency, which left as many as 30,000 dead.

But as the Turks were busy putting down the Kurds in Turkey, the Kurds in Iraq were busy setting up a state within a state. Turkish leaders have watched the thriving Iraqi Kurds with greater and greater suspicion. In 1997, Turkish troops crossed the border to hunt down suspected Kurdish militants. The Turkish soldiers, some 1,200 of them, have been there ever since.

Failing assurances from the Americans to block any attempt by the Kurds to form their own state, the Turks appear ready to take matters into their own hands.

In recent weeks, Turkish leaders have publicly pledged to send twice the number of Turkish troops into northern Iraq as the Americans. They have also promised to protect the region's Turkmen population, which would bring the Turkish Army deep into Iraq.

In the end, some Turkish commentators say, the negotiations with the Americans are hampered by a lack of trust. The Kurdish region of northern Iraq has flourished under the encouragement of successive American presidents, who have seen it as a bulwark against Mr. Hussein.

If war comes to Iraq, these Turkish commentators say, many in the Turkish government fear that the Americans, rather than blocking the Kurdish bids for a new state, would try to help them along.

"The Turks do not trust the Americans to be an honest broker," said Dogu Ergil, professor of political science here. "And they don't believe Turkey will be in control of northern Iraq once Saddam is gone."

But Turkey has a lot at stake. In the last Persian Gulf war in 1991, Turkey came out a loser. The economic sanctions that followed closed off Turkish trade with Iraq, one of its closest trading partners. Northern Iraq fell into the control of Kurdish nationalists, which is bad news for a country with its own restive Kurdish minority.

This time, Turkey fears even worse consequences from war. If a post-Saddam Hussein Iraq breaks up, the Iraqi Kurds could make a bid for statehood, stirring up their ethnic cousins in Turkey. The economy could take a serious hit as oil prices soar and tourism falls. One Turkish business group puts the potential cost to Turkey at $16-billion.

Then there are the political dangers. Nine in 10 Turks say they oppose war with Iraq, so the newly elected government would be going way out on a limb by letting the Americans use Turkey as a springboard. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, leader of the ruling party that has its roots in Islamism, badly needs something to show for its concessions if he goes along with an unpopular war.

But if the risks of welcoming the United States are high, the risk of defying it may be higher. Losing Turkey as a base would cost the United States time, money and, quite possibly, lives. A bitter Washington might well turn a cold shoulder to Turkey as it struggles with its ongoing economic crisis, and Turkey needs U.S. support in its talks with international lenders over a $16-billion debt.

If the Americans have to invade Iraq only from the south, it might mean a longer war and more damage to Turkish interests. Refugees from Iraq might pour across Turkey's borders. The Kurds might gain control of valuable northern Iraqi oilfields. Turkish troops might be drawn into the fighting as the Americans push up from the south.

If it helps Washington, on the other hand, Turkey can expect U.S. help in defending its border with Iraq. It might also gain more say over what happens in the Kurdish lands of Iraq after the war. To that end, Turkey wants its own troops to help patrol northern Iraq.

The best carpet sellers know just how long to hold out before lowering the price. If Turkey follows its interests, it will strike a deal before the customer walks out the door.

The Fierce Kurdish Vision

Some major events in recent Kurdish history:

1843-49 The Ottoman Sultan destroys a series of Kurdish principalities.

1908 Kurdish political clubs are established in Istanbul, Mosul, Diyarbakir and Baghdad in an attempt to organize a national movement.

1918 World War I ends, and the Ottomans and their allies surrender. A joint French and British declaration calls for the "liberation of the peoples oppressed." Kurdish chiefs demand national rights.

1923 Turkey is declared a republic under Mustafa Kemal. The Treaty of Lausanne between the Allies recognizes Turkish sovereignty and formalizes the division of Kurdish areas.

1925 The Turkish Army crushes a Kurdish revolt in the south. The League of Nations adopts the border line between Turkey and Iraq, annexing Mosul to Iraq despite resistance by Kurds.

1945 Kurds submit a memo to the United Nations demanding national rights.

1946 Kurds proclaim a republic in the Iranian city of Mahabad, receiving training and equipment from the Soviet Union. Iranian forces crush the republic in December.

1961 Iraqi Kurds revolt, accusing the government of failing to honor agreements.

1970 An agreement with Iraq ends fighting; limited Kurdish self-rule is established.

1979 The Islamic Revolution in Iran prompts a Kurdish uprising that is crushed by Revolutionary Guards.

1984 The Kurdistan Workers Party, a militant group, begins a violent campaign for independence in southeast Turkey.

1988 Saddam Hussein's forces attack Kurds in Halabja with chemical weapons, killing thousands. After the Iran-Iraq War ends, thousands of Kurds flee to Turkey, fearing a crackdown.

1991 U.S.-led forces drive the Iraqi army from Kuwait, and Baghdad moves forces north for a crackdown against Kurds. The United Nations establishes a save haven for Kurds in the north.

1994 Open fighting erupts between rival Kurdish groups.

1998 A peace agreement is signed in Washington on Sept. 17 between the main Kurdish leaders.

1999 Turkey captures Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the Kurdistan Workers Party. Mr. Ocalan urges rebels to withdraw from Turkey and seek independence through political channels.

2002 Turkey lifts a 15-year state of emergency over the Kurdish uprising in the country's southeast.

Source: Associated Press and The New York Times

![]()

6. - The Guardian - "Turkey's leader blames EU for failing to give political support in crisis":

ANKARA / 21 February 2003 / by Helena Smith

Turkey's de facto leader, Tayyip Erdogan, yesterday lashed out at

Europe for failing to provide it with the necessary political support

to confront the crisis over Iraq.

Mr Erdogan said the EU's refusal to give Ankara a concrete date for accession talks as a candidate country had backfired because Turkey now had less clout to stand up to America, its longstanding Nato ally.

In an interview with the Guardian, Mr Erdogan complained that his country would be far better equipped to deal with the crisis over whether the US military should be allowed to use Turkish bases if the EU had opened the door to Turkish accession to the union at the Copenhagen summit last December.

"The United States is our friend," he said. "But if Turkey had received a date, if Turkey was strong in its relations with Europe, knew it was a part of Europe and could act with Europe to eliminate the presence of weapons of mass destruction, a better road map could be prepared for the rest of the world regarding a solution to this crisis."

For several weeks Ankara and Washington have been embroiled in what many diplomats have described as "unseemly haggling" over the amount of money Turkey will receive in grants and credits for allowing US soldiers to be deployed there.

This week the US secretary of state, Colin Powell, announced that Washington was willing to make a "final offer" of $6bn in grants and $20bn in loans - $6bn short of Turkish demands.

Mr Erdogan, who is expected to be elected prime minister after running in a by-election next month, said Turkey not only faced immense US pressure to host thousands of combat troops in the event of conflict but the prospect of catastrophe for its economy, which has yet to recover from the first Gulf war.

In a message to Washington, Mr Erdogan said he was utterly opposed to military action against his neighbour. "We may not approve of the regime in Iraq but that doesn't mean we see it as our responsibility to remove. Put simply, we do not want the 21st century to be a century of war."

Mr Erdogan said it was wrong to think that Turkey's infant government was intent only on bargaining for more financial aid from America in exchange for help in a possible war. US military planners say opening a northern front from Turkey is vital to ensure that any invasion of Iraq is swift.

"Our discussions [with the US] are not only economic. They also have political, military and social dimensions - on a political level we want to ensure the integrity of Iraq," said Mr Erdogan. "We have to come up with some strong reasons for our parliament to vote on [stationing US troops]."

The ruling AK party controls 363 of the 550 seats in Ankara's parliament and unlike any of its predecessors has excellent relations with the Islamic world.

But Turkey fears that if Iraqi Kurds assume control of the country's rich oil resources it will not only empower them to proclaim independence but stir up similar secessionist sentiment among its own predominantly Kurdish population in the south-east.

Since 1984 30,000 Turks have died in a guerrilla war waged by Kurdish separatists which some say despite a ceas fire has already been reignited with all the talk of war.

Fearing the worst, Ankara has deployed an estimated 5,000 troops to northern Iraq. Post-war, Turkey will almost certainly move in to ensure that any attempt at independence by the Iraqi Kurds is quashed, regional analysts say.

Anti-war sentiment is not only running high in Turkey but apparently growing by the day.

"About 95% of the Turkish people are opposed to a

war because they still remember the effects of the first [Gulf] war,"

said Mr Erdogan. ![]()

7. - The New York Times - "Flashback for the Kurds":

WASHINGTON / 19 February 2003 / by Peter W. Galbraith*

As the Bush administration struggles to induce Turkey to support

a war with Iraq, our Kurdish allies in northern Iraq are realizing that

once again America is about to double-cross them.

Zalmay Khalilzad, President Bush's special envoy to the Iraqi opposition, went to Ankara this month and told top Kurdish leaders to accept a large deployment of Turkish troops supposedly for humanitarian relief to enter northern Iraq after any American invasion. He also told the Kurds that they would have to give up plans for self-government, adding that hundreds of thousands of people driven from their homes by Saddam Hussein would not be able to return to them.

For the Kurds, this brought bitter memories. They blame Henry Kissinger for encouraging them to rebel in the early 1970's and then acquiescing quietly as the shah of Iran made a deal with Iraq and stopped funneling American aid to them. (Mr. Kissinger's standing among Kurds was not helped by his explanation: "Covert action should not be confused with missionary work.")

After the Persian Gulf war, the first President Bush called on the Iraqi people to overthrow Saddam Hussein. When the Kurds tried to do just that, the American military let the Iraqis send out helicopter gunships to annihilate them. Mr. Bush partly salvaged his standing with the Kurds a month later when he cleared Iraqi forces from the region, thus enabling the creation of the first Kurdish-governed territory in modern history.

In the latest buildup to war, the Kurds took comfort from their special status as the only Iraqi opposition group to control a territory, to possess a significant population and to have a substantial military force. Kurdish leaders have been courted at the highest levels, meeting with Vice President Dick Cheney and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. But American support hit a wall: Turkish consent to the deployment of American troops for a northern front against Iraq is considered an important, although probably not essential, element in American planning. In addition to billions in cash, Turkey has demanded an ironclad assurance that there will not be a separate Kurdish state.

The Kurds did their best to meet Turkish and American concerns. They promised they would not seek independence, confining their ambitions to a self-governing entity within a federal Iraq. They also promised not to take Kirkuk, an oil-rich city they describe as their Jerusalem.

However, this proved inadequate for the Turks. They fear that federalism could be a way station to Kurdish independence and they may be right. The four million Kurds who live in the self-governing area overwhelmingly do not want to be Iraqis. After 12 years of freedom, the younger people have no Iraqi identity and many do not speak Arabic. The older generation associates Iraq with poison gas and mass executions.

Still, seeing the Kurds as an easier mark, Washington sided with Turkey. The Kurds were told that federalism would have to wait for deliberation by a postwar elected Iraqi parliament, in which they would be a minority.

But the Bush administration may have gotten the power calculus wrong. The Kurds have established a real state within a state, with an administration that performs all governmental responsibilities, from education to law enforcement. Their militias number 70,000 to 130,000, and there is a real risk of clashes with any Turkish "humanitarian" force. The democratically elected Kurdistan assembly has already completed work on a constitution for the region that would delegate minimal powers to a central government in Baghdad, and could submit it for a popular vote. Short of arresting Kurdish leaders and the assembly, an American occupation force may have no practical way of preventing the Kurds from going ahead with their federalist project.

And now it seems Turkey's financial demands may exceed what Washington is willing to pay, and Turkey will sit out the war. That could weaken Turkey's influence in creating a postwar Iraq, and improve the Kurds' prospects for self-rule.

President Bush's war has always had a moral component to it: the liberation of the Iraqi people from a brutal regime. If it sides so completely with Turkey in putting down the democratic hopes of Iraq's Kurds, the administration looks shortsighted and cynical. And not just to the Kurds.

* Peter W. Galbraith is a former United States ambassador

to Croatia. ![]()

8. - The Christian Sience Monitor - "A film puts faces on unseen street children":

ISTANBUL / 20 February 2003 / by Ilene R. Prusher

On the edge of Istiklal, home to many of Istanbul's hippest clubs,

a teenage boy named Hassan Dogan Yildiz sways and stumbles as though

standing on a boat at sea.

He lifts a blackened hand and holds a cloth to his nose and mouth, as though to keep warm. But the cloth is soaked with glue, and as the piercing smell rises, a shopkeeper hastily offers a free pastry to make him go away.

There isn't much that keeps Hassan - or some 15,000 other children living on the streets - from capsizing completely. And it is having watched children get pulled under that spurred Umit Cin Guven to make "Children of Secret," a haunting portrayal of kids surviving on a diet of drugs, donations - and theft.

The film, which has won several Turkish awards, was Mr. Guven's way of trying to expose a dark underside of Turkish society. A largely con- servative Muslim nation run by a central government seen as the defender of its citizens' interests, Turkey is not accustomed to acknowledging that so many young people may be struggling to survive on their own. And experts say the country's economic crisis, which many Turks suspect will only worsen in any war against Iraq, is increasing the number of children who leave home and end up in places like the one Hassan lives in: the dark, dank lobby of an abandoned building.

"My aim was to put this on the agenda," Guven says over a glass of tea on an Istiklal side street. "There has never been an official recognition of this problem. Our idea was to show the government that something should be done for these kids, to wake up the public, to make people do something. This is not only the government problem, it's the whole system's problem."

Spurred on by personal experience

Guven, a boyish-looking Turk in his late 20s, was headed home on a cold February day a few years ago when he saw a boy sleeping in a phone booth. "I felt sorry for him because it was very cold," Guven recalls, dark brown eyes tightening at the memory. The following day, he learned that the boy in the booth had frozen to death overnight.

"I felt terrible. I can't even find the words to describe what I felt," he says. "Maybe giving this kid a blanket would have prevented him from dying. People in the neighborhood were so unemotional about it.... And I realized that something should be done for [other kids like him]."

The resulting film explores the fragile lives of street children - as well, often, of their families - through the story of a 10-year-old boy named Cemil, who runs away from home because of an abusive stepfather. He is taken in by other street children, who start trying to raise money to send him home. Meanwhile, his mother, who comes to Istanbul to look for him, faces her own struggles as she is pursued by her former brothers-in-law, who feel her divorce hurt the family honor.

Picking up on daily rhythms

Guven started his research for the film by spending time in places where streets kids hang out, trying to work his way into their world. For months, they simply avoided this odd guy who was following them around, obviously too clean and coherent to be one of them.

Playing anthropologist, Guven noticed their patterns: They had specific days designated for bathing or washing their clothes, a loose code of ethics to help one another out, and a regular cycle: sleep by day, get high and beg for cash - or steal - at night.

But perhaps Guven's most important discovery was the ultimate interpreter: a former street kid who managed to turn his life around.

Ersin Salah Altinok ran away when he was 9 years old, and spent the next 23 years on the streets.

Today, he looks a decade older than he is, and bears ear-to-ear scars from a knife fight that came close to killing him. In addition to serving as a consultant on the film, Mr. Altinok works for Hope for Children, a private organization aimed at giving shelter and rehabilitation services to street children.

"At first, I didn't think it would be a good idea at all, to aid in making this film," he says. "I really believed that no one had ever cared about us and that a filmmaker would only come along and show our bad side."

Some government assistance

According to Altinok, there was never a time when surviving on the streets was easy.

As children, Altinok and his comrades stole flowers from cemeteries and sold them to pay for food and drugs.

But since he was a teenager, he says, the number of street children, and the prevalence of drug use among them, have burgeoned, driving more of them to crime. Run-ins with the police are common, and teenagers on the street say they're often beaten by local cops.

In the past five years, Turkish government agencies have launched programs aimed at helping street children. Some get assistance in returning to their families, while others are given shelter and access to remedial education. Officials at the child-protection center in Istanbul say they have worked with 3,000 children in some capacity.

The majority of the children on the street are of Kurdish descent, Altinok says, and like him, come from the poorer corners of southeastern Turkey. Many come from large rural families, who sometimes push a troublesome child to seek work in the big city.

The children who can be seen working the intersections of Turkish cities shining shoes and selling tissues are usually better off: Many are younger and dutifully bring their earnings back to their families.

But by the time they reach their teen years, many end up getting used to the harsh and lawless side of street life and fall into drug abuse.

"Whether you sniff or take pills, you're in space and out of control, and it causes you to misunderstand people. I've seen friends killed in fights because of that, and in one year, we lost six people," Altinok says. "I'm not proud of this kind of life. I only talk about it so the families won't let their kids go out on the street."

But many do, and Altinok admits that even he was not receptive to his brother's attempts to bring him home.

It can be equally difficult to understand what brought Hassan here.

Unanswered questions

Altinok, who knows Hassan and the other boys in the neighborhood, stops him on a chilly night and asks him about the raw scabs across his lips and face.

There was some argument, Hassan says, and another kid took a piece of plastic out of the fire and threw it at him.

"Will it be OK?" Hassan asks, emitting a puff of vile chemical air. His eyes on a vacant trip, his walk a hesitating stumble, he sits down on a bench to respond to questions he says he cannot answer.

How long has he been on the streets? "I don't even know what I had for breakfast," he slurs. He is the fifth in a family of nine, but he will not say where they are. "I don't think they will find me," he says. "It was my choice to live on the streets." What does he want? "I want nothing," he says.

Does his family know he's here? "Don't ask me about my family!" he explodes, and charges off into the numbing night.

Here, as in his film, Guven warns, there are not many happy endings.

"The end of a street kid is jail or death,"

he says. "It's rare to find one who has reached the age of 30."

![]()