7

March 2003

![]()

1. "A pivotal nation goes into a spin", whatever path Turkey's government chooses, it is bound to face howls of protest.

2. "Turks versus Kurds", by Julian Manyon.

3. "Iran-Backed Militia Seen Moving Into Iraqi Kurdish Zone", the Badr Brigade, an Iraqi Shiite militia sponsored by Iran and pledged to combat President Saddam Hussein's rule, seems to be on the move. Its fighters have been waiting for two decades, most intently since southern Iraq's Shiite population rose up against Hussein after the 1991 Persian Gulf War -- only to be crushed by Baghdad's security forces while the United States stood by.

4. "Iraq Kurds vow to fight Turks, U.S. troops or not", Iraqi Kurds have vowed to fight Turkish troops that come into their self-governing area, especially if they come without U.S. allies.

5. "Turkey's Erdogan seeks official political return in by-election", the head of Turkey's ruling AKP party, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is set to stage his return to official politics in a parliamentary by-election here Sunday and then take over the prime minister's post.

6. "Cypriot sides confer", ahead of summit, Turks back Denktash’s hardline stance.

1. - The Economist - "A pivotal nation goes into a spin":

Whatever path Turkey's government chooses, it is bound to face howls of protest

6 February 2003

WHEN Turkey's parliament narrowly rejected a government motion on

March 1st to let 62,000 American troops on to Turkish soil, a wave of

euphoria swept the country, because a good 90% of its people—so

say the pollsters—vehemently oppose an American-led war in Iraq.

But the joy was short-lived. With dozens of American warships still

anchored off Turkey's eastern Mediterranean shores, pressure began mounting

on the country's ruling Justice and Development Party to resubmit the

bill or risk wrecking relations with the country's most influential

friend, the United States. For Turkey's leaders know that, without American

co-operation, hopes of rapid economic recovery will recede. And so—just

as important, in many Turkish eyes—would Turkey's chance of having

a big say in the future of Iraq, its troubling neighbour.

On March 5th, Turkey's top general, Hilmi Ozkok, weighed in on the American side, saying he favoured letting the Americans open a second front against Iraqi forces in Kurdish-controlled northern Iraq, with Turkey as the launch-pad. The odd thing about his statement was that he and his fellow generals had refrained from speaking up earlier. Well, they said, they had not wanted to intimidate parliament.

Many generals, in any event, still doubt the sincerity of the ruling party's recent enthusiasm for a secular Turkey, since its roots are Islamist and the party's leader, Tayyip Erdogan, started his career in a zealously Islamist party. Moreover, not all generals take a pro-American line on Iraq. “Once the Americans come they will never leave,” says Kemal Yavuz, a retired general who is strongly against the war. “We don't know where the military or the government really stands in all of this,” says one weary American diplomat.

So what next? Mr Erdogan is still in a pickle. He faces a by-election on March 9th. Five years ago he was barred by a security court from being an MP and therefore from becoming prime minister, because of a conviction for allegedly seeking to incite religious hatred by a poem he recited in 1997. If he again wins a seat, it is understood that he will be let back into parliament (the constitutional article under which he was convicted was amended last year) and should become prime minister within a week or so. Hitherto, he has pulled the strings behind the scenes.

But should he, with the generals' blessing, press for a second vote on the bill before his by-election or wait until his premiership is in the bag? He has to weigh several factors. First, would the Americans wait that long? Just as General Ozkok was making his speech, they had begun to divert some of their ships towards the Suez canal, presumably en route to the Gulf. And the Americans have let it be known that they could still open a northern front by airlifting troops into the mainly Kurdish north of Iraq, and would bank on the Kurdish militia operating there for support.

In any event, whatever the timing of a second bill and however hard the generals now urge MPs to pass it, it would still not be sure to get through. Another defeat in parliament would be a huge blow to Mr Erdogan's leadership, whether or not he had become prime minister. It could even cause the government to fall.

Mr Erdogan plainly misjudged the first vote. He had confidently declared that it would be approved just hours before it was rejected. In the event, 264 MPs did vote in favour and 250 were against, but the presence of 19 abstainers meant that the government had failed by three votes to get a simple majority of all those in the chamber at the time.

With friends like these...

Mr Erdogan had underestimated the strength of dissent within his own Justice and Development Party, better known by its initials AK, some 100 of whose members rebelled. Many were from the Kurdish south-east, and were not so much against American troops coming into Turkey as Turkish ones going into northern Iraq.

Bulent Arinc, a mercurial AK man who is parliament's speaker, made no secret of his delight at the government's humiliation. A fiery advocate of lifting the ban on the Islamic-style headscarf in public institutions, he has a lot of support in the party. Barely an hour after General Ozkok's remarks, he said he was still loth to let parliament debate the bill again, and spoke scathingly of “the war lobby”.

Indeed, he noted, predictions that the Turkish lira would collapse as a result of the no vote and thus bring a fresh financial crisis had proved false. And, though Istanbul's stockmarket dived by 10% just after the vote, it soon began to recover; the lira has since held fairly steady against the dollar, thanks to intervention by the central bank. The IMF further boosted confidence when it said it was happy with a new budget unveiled this week.

But the Americans still have means of persuasion. They made it clear that an aid package worth $6 billion which was meant to cushion the financial effects of a war would be shelved, that the Pentagon would no longer approve the idea (mandated by the quashed motion in parliament) of thousands of Turkish troops crossing into northern Iraq, and that Turkey would have virtually no say in shaping Iraq's future. After the no vote, American military engineers who had begun upgrading Turkish ports in preparation for disembarking troops stopped work.

Old pals fall out

It will take a long time for the wounds opened by the American-Turkish row to heal. The Turks think that the Americans have been clod-hopping and insensitive. Even before the vote, haggling over petty issues had become bitter.

And for all of America's repeated assurances that it does not back the idea of an independent Kurdish state, many of Turkey's generals are suspicious. Some Turkish officials suggest that a wave of anti-Turkish demonstrations in northern Iraq have been encouraged by what one has described as “US agents” in the region.

To make matters more awkward between the Americans and the bruised Turkish government, Turkey's generals seem determined—whatever the Americans say—to wade into northern Iraq. According to some Turkish reports, around 20,000 Turkish troops have already crossed the border. The Iraqi Kurds say they will fight back. Turkey's main rival in the region, Iran, will certainly use its own friends in the Kurdish enclave in northern Iraq to compete for influence.

Nor, despite its spat with America, is Turkey winning

plaudits in Europe, particularly since it has failed so far to prod

Rauf Denktash, the Turkish-Cypriot leader, into agreeing to a settlement

in Cyprus (see article). If, however, Mr Erdogan took the risk, before

or after his by-election, of resubmitting the bill to let in American

troops, he would take a lot of flak from rebels in his own party and

from his compatriots at large. Many Turks would then furiously charge

him with trampling on democracy and cowering before bankers, generals

and bullying Americans. Mr Erdogan has a rough fortnight ahead of him.

![]()

2. - The Spectator - "Turks versus Kurds":

ERBIL / 8 February 2003 / by Julian Manyon

ON the road to ancient Nineveh, now signposted Mosul, I stood with

a group of Kurdish Peshmerga soldiers watching one of the acts of spite

which still mark the Saddam Hussein regime, even in what appear to be

its death throes. We were at one end of the long bridge that separates

the two sides, looking towards the high ground half a mile away, where

Iraqi troops, visible as tiny silhouettes, man a line of bunkers and

blockhouses. At the other end of the bridge, Iraqi soldiers were searching

the few vehicles allowed to cross, ripping out the door panels and emptying

the petrol tanks, leaving just enough fuel for the drivers to reach

the Kurdish side. At 5 p.m. the bridge closed, and with a sudden whoosh

of flame the Iraqis set light to the hundreds of gallons of fuel they

had stolen during the day. A column of black smoke rose into the sky.

The message to the Kurds: you may be short of fuel but we have fuel

to burn.

Saddam’s troops may be able to taunt the Kurds for a little longer than expected. The area around Mosul, Iraq’s second city, was supposed to be the main target of a massive armoured thrust by the US 4th Infantry Division, whose tanks should by now have been revving their engines at the Turkish border. Instead, American attempts to pressure the Turks into acquiescence have so far resulted in fiasco and, at the time of writing, an armada of supply ships carrying the 4th Infantry Division’s equipment is steaming in slow circles around Cyprus, while Pentagon planners wonder what part if any it will play in the crusade against Saddam. Donald Rumsfeld has certainly achieved his strategic aim of being ‘unpredictable’, but perhaps not in the way he intended.

Bullying the Turks has often been a difficult exercise, as Winston Churchill learnt to the British army’s cost in the first world war. Today’s Turkish leaders, who were swept to power by the electoral triumph of the Justice & Development party, have political roots in the Islamist movement and regard American war plans with prickly suspicion — feelings which, it seems, can be assuaged only by large amounts of cash. American negotiators were taken aback by the Turks’ sharp reminder that much of the money they were promised in 1991 had never materialised, and that this time the $6 billion they were to receive for allowing the US troops ashore must be paid in full. And the Turks made clear that all the details of the agreement should be fully thrashed out in advance. The leading light of the Justice & Development party, Tayyip Erdogan, declared that the talks ‘are not things to be rushed because a phone call comes’, an apparent reference to yet another insistent call from Colin Powell to the Turkish Prime Minister, Abdullah Gul. ‘Just as the US Congress can take six to eight weeks to reach a decision,’ Erdogan said, ‘we are going to discuss every detail.’ But in Washington the virtue of patience is no longer associated with diplomacy. Convinced that no politician in bankrupt Turkey could ignore the consequences of snubbing the United States, and driven by a relentless Pentagon timetable which demands war before the onset of hot weather in southern Iraq in April, the Americans blundered.

They arm-twisted the Turks into holding a parliamentary vote, and lost. Washington is now doing its best to put on a brave face. There is talk of diverting the 4th Infantry Division to Kuwait, or of success in a hoped-for second vote. But there is no disguising the body-blow which Turkish democracy, previously hailed as a beacon in the region, has dealt to American plans. The original war plan called for swift, devastating blows from both north and south. The key objectives, apart from killing or capturing Saddam, were to stun and dismember the Iraqi armed forces and, crucially, to secure the major oilfields before the Iraqi dictator could fire them. The latter is particularly important since, in the absence of international support for the operation, much of the cost of Iraq’s reconstruction and the American occupation will have to be met by rapidly boosting the country’s oil production. A key area is the great oilfield around the northern city of Kirkuk, with its hundreds of wells and ten billion barrels of proven reserves. It has apparently been hoped to secure it with an airborne assault, quickly supported by heavy armour on the ground. Now, unless the Turks relent, there will be no giant M1A tanks to crush resistance, and American planners will have to decide whether to put the airborne into the cauldron on their own. Standing at the northern edge of the oilfield, at the furthest extent of Kurdish-held territory, I witnessed an ominous sight. Rising some ten miles away was a great column of smoke from a huge oil fire. The Iraqi authorities have reported this as an ‘accident’. The Kurds say it is Saddam’s warning to America and Britain of what will happen when the invasion begins.

There will still be a northern front. Contingency plans are being drawn up to fly lighter American units directly to airfields here in the Kurdish-controlled area, but the absence of a full-scale armoured punch could prolong the war, perhaps allowing forces loyal to Saddam to mount some sort of resistance in the dictator’s Sunnite heartland around Tikrit and in other northern cities. It is likely that when Washington’s red mist over the lost vote has cleared, an improved offer will be on its way to Ankara, where the Justice & Development party now seems to be making some effort to impose discipline on its disorderly ranks. But in this mosaic of ethnic hatreds in which President Bush has chosen to launch his imperial adventure, a deal with the Turks could provoke serious trouble in northern Iraq. A key Turkish demand is to station some 80,000 of their troops inside Kurdistan with the ostensible purpose of protecting Turkey from a flood of refugees. But for the Kurds, who cherish the freedom they now enjoy here, this smacks of occupation and even a disguised attempt to take back the ‘vilayet’ of Mosul — effectively the whole of northern Iraq — which the British wrested from Ottoman control in 1918. (Anyone who imagines this to be a long-forgotten grievance has only to read the Turkish newspapers which crowed triumphantly when their government announced that one of the many conditions in the negotiations with Washington was that British troops should not transit through Turkey to northern Iraq.)

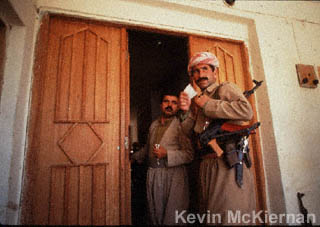

To most Kurds, the prospect of thousands of Turkish soldiers entering their hard-won homeland is unacceptable. Among the many who have told me that they will take up arms to fight them is my own driver, Necmedin, an otherwise friendly and kind-hearted man, who announced as we passed the small Turkish military outpost already stationed in Erbil, ‘We will start by killing them.’

Meanwhile, the Kurds have their eyes fixed on the gains they may make in the event of war. Near Mosul is a string of formerly Kurdish villages which were ethnically cleansed by Saddam Hussein in 1975 and then settled by Arabs given small grants to move there. One of these villages, a jumble of mud-brick huts surrounding a stone fort topped with an Iraqi flag, sits right on the borderline with Kurdish-held territory. I was taken to within 50 yards of it by a Kurdish commander, a smiling bear of a man, who showed me the proclamation, written in Arabic, that he has issued to the inhabitants. It tells them curtly to pack up and leave or he will not be responsible for the consequences. Arab children played football only a short distance away, but the commander’s mind was fixed on the injustices of almost 30 years ago. ‘If the Americans and British attack, we will take back our land,’ he told me. ‘And what about Kirkuk?’ I asked him, knowing that I was touching a nerve. ‘Kirkuk is our heart,’ he said, ‘we will take that back, too.’

As the pressure mounts, the small town of Erbil where

we are quartered remains surprisingly calm. In fact, the only signs

of war fever are being shown by the two American cable news networks

which are locked in fierce competition. CNN has taken over a small hotel

and placed guards at the gates, while the upstart Fox News, a channel

which mixes gobbets of information with mesmeric rantings about the

urgent need for war, has fortified a section of a larger building. For

days, residents of the Erbil Tower Hotel have been woken by a crane

lifting sandbags to the fourth floor. The result is reminiscent of General

Percival’s ill-fated ‘battle-box’ during the Japanese

seige of Singapore. The doorway and every external wall are heavily

sandbagged, with only the occasional slit allowing light to enter. Fox

staff dismiss fears that the hotel may collapse under the weight, and

mutter darkly about extremist groups and car bombs. Fox News is said

to be Donald Rumsfeld’s favourite television channel, and I left

wondering if their efforts stem from paranoia or if they really know

something that I don’t. ![]()

3. - The Washington Post - "Iran-Backed Militia Seen Moving Into Iraqi Kurdish Zone":

BANI BEE / 7 March 2003 / by Karl Vick

The fighters arrived in the night from Iran, local Kurds say, filling

more than 100 white canvas tents that have sprung up in neat rows here

over the past week. Visible from the road, the new arrivals to this

autonomous stretch of northern Iraq go about their military routines

in fresh camouflage uniforms, cleaning AK-47 assault rifles under a

bright winter sun.

The Badr Brigade, an Iraqi Shiite militia sponsored by Iran and pledged to combat President Saddam Hussein's rule, seems to be on the move. Its fighters have been waiting for two decades, most intently since southern Iraq's Shiite population rose up against Hussein after the 1991 Persian Gulf War -- only to be crushed by Baghdad's security forces while the United States stood by.

A smuggler at the border of northern Iraq and Iran, spiriting crates of television sets to Iran, said he recently saw four green buses loaded with militiamen entering Iraq. It was 2:30 a.m., said the smuggler, who asked not to be identified further, and the convoy carried a 57mm antiaircraft gun.

Estimates of the Badr Brigade's overall strength range from 5,000 to 30,000, but Kurdish officials say that only several hundred have arrived at this little town 40 miles south of Sulaymaniyah and 11 miles west of the Iranian border. The brigade's overall leader, Ayatollah Mohammed Bakir Hakim of the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, said in an interview last month at his Tehran headquarters that most of the militia is already living in Iraq, ready to retrieve hidden weapons and spring into action at a moment's notice.

"Our forces have been ready for a long time, for nearly 20 years," Hakim said.

Whatever its numbers and readiness, the lightly armed Badr militia would not figure as a major military factor in a U.S.-led campaign for control of Iraq. But its armed groups could cause civil unrest, which many analysts call the biggest challenge U.S. forces would likely face in this nation of 23 million people in the event of a victory over Hussein's government.

Iran, which arms Hakim and his militia, maintains a position of "active neutrality" on the question of a U.S.-led war against Iraq. Diplomats smile at the phrase, which contains the tension between Iran's official distaste for what it describes as U.S. "unilateralism" and its relish at the potential demise of Hussein's government, which it battled from 1980 to 1988.

Unlike Turkey, which is preparing to send tens of thousands of troops into northern Iraq in the event of war to guarantee its interests, Iran has made no move to involve itself directly. But it has hosted the Badr Brigade since 1983 and made clear that it, too, has interests in Iraq.

"If anyone is seen dabbling, the Iranians will dabble, too," said a foreign diplomat in Tehran.

"The Iranians are very cynical," said a Kurdish official who asked not to be identified further. "They do a lot of fishing in troubled waters."

The affinity between Tehran and Hakim's group is natural: Iran is mostly Shiite and is run by the Shiite clergy. Hakim's organization says it represents the Shiites who make up more than 50 percent of Iraq's population, particularly in the south near Kuwait. Its move into northern Iraq seems designed to ensure that the country's Shiites get their say in whatever might be organized if Hussein's Baath Party government is destroyed -- and that Iran's interests are not neglected in the process.

"They have to go" into Iraq, said Asadullah Athary Maryan, an adviser to the Iranian Defense Ministry, referring to the Badr exiles moving in from Iran. "If they don't participate in the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, they are losers."

"The Shiites in the south of Iraq are Iran's aces, but they are not Iran's servants," Maryan said. "They do not obey Iran. They are really Iraqis, not Iranians, and we understand that. All they want to do is persuade the Iraqi people that they are not puppets of the Americans, that they think independently. They want to come back and say, 'We are legitimate. We helped throw out Saddam.' "

That posture unsettles U.S. war planners, who welcomed Hakim's organization into the U.S.-backed opposition to Baghdad but also asked all armed groups inside Iraq to leave the fighting to U.S. forces now massing in Kuwait. Kurdish parties, which administer this part of Iraq under the protection of U.S. and British fighter patrols, have promised to obey, vowing to keep their 70,000 fighters in a defensive posture. But the disposition of the Badr force is less clear.

In the closing days of the Gulf War, mobs in the overwhelmingly Shiite south rampaged against Hussein's administration, lynching officials and former tormentors in a spate of revenge killings that ended only when Iraqi forces struck back from helicopter gunships. Worries of a replay have helped drive U.S. plans for the impending conflict. For example, a British-led force is tasked to secure Basra, the largest city in southern Iraq.

In the interview, Hakim repeatedly declined to say whether Badr forces would defer to U.S.-led forces. He emphasized that the lack of U.S. support in 1991 is influencing Shiite preparations now.

"The people are suspecting the American role because in 1991 they supported the Iraqi regime when it was killing nearly half a million in front of American eyes," Hakim said. "In 1991, the United States did not have the will to make the change inside Iraq."

Hakim also termed "dangerous" a U.S. plan to install an American general as governor of Iraq while a transitional government is put in place. Both Hakim and Iran have urged prompt elections.

Reports of the Badr deployment prompted a fresh warning from the State Department last month. Richard Boucher, the department's spokesman, said the United States "would oppose any Iranian-supported presence" in Iraq. He said a Badr deployment "would be a very serious and destabilizing development."

That may explain why Hakim's local office, in the northern

city of Sulaymaniyah, denied that the militiamen were arriving. Hakim's

representative, Abu Mohammed Kharsani, said the brigade's only presence

in northern Iraq was a small outpost in the town of Maydan Saray, three

miles south of here, that was established more than 10 years ago. But

reporters in Sulaymaniyah last week saw young Badr militiamen climb

off buses from the border and disperse into neighborhoods. ![]()

4. - Reuters - "Iraq Kurds vow to fight Turks, U.S. troops or not":

ARBIL / 6 March 2003 / by Sebastian Alison

Iraqi Kurds have vowed to fight Turkish troops that come into their

self-governing area, especially if they come without U.S. allies.

Sami Abdul-Rahman, deputy premier of the Kurdistan regional government, told Reuters late on Wednesday Kurds were extremely worried by Turkey's stated aim of sending troops if there is a war and would resist "military occupation" by any means.

Turkey says its troops would prevent a flood of Kurdish refugees entering Turkey, if there is a U.S.-led war to overthrow President Saddam Hussein, and to protect Kurdistan's Turkmen minority, culturally and linguistically close to Turks.

Ankara also wants to stop any attempt to establish a Kurdish homeland, mindful of possible consequences among its own large Kurdish minority, although Iraq's Kurds -- a majority in the north -- say they have no plans to do so.

Turkish troops would enter with U.S. forces, but U.S. plans for a second, northern front in Iraq are in question since Ankara's parliament voted against letting 62,000 U.S. troops use Turkish territory. A possible second vote might overturn this.

The refusal to allow U.S. troops into Turkey has raised fears among Kurds that Turkish forces will come in alone.

"I am still very very worried and concerned," Abdul-Rahman told Reuters over tea and fruit at his home in Arbil, the largest city in Kurdish-administered Iraq.

"Whichever way the Turks come, our people will resist them with all means at our disposal. Believe me, if we are faced with death or military occupation, the first would be lighter."

He said it would complicate an anti-Saddam coalition if Kurds and Turks fought each other in the middle of a larger war.

"It would be worse if they came with the Americans. We don't want to be seen to be fighting part of the coalition," he said.

He added that Turkey has already said its troops will not fight the Iraqi army if it entered Iraq.

"So what are they coming for? To repress Kurds," he said.

If fighting between Turks and Kurds erupted, Abdul-Rahman said he did not believe neighbouring countries would stand idly by, adding that it could lead to "a major regional conflict".

OIL WORRIES

Some analysts fear that if war breaks out, Kurdish forces could try to retake Kirkuk, the main centre of northern Iraq's oil industry and historically a Kurdish city, but from which thousands of Kurds have been expelled by Saddam.

This has raised fears that Turkey, through which Kirkuk's oil is exported to world markets, could intervene, leading to fighting over the city and significant loss of oil production -- Kirkuk produces around 800,000 barrels per day of crude oil.

Abdul-Rahman said that although Kurds regarded Kirkuk as Kurdish, "there are no contingency plans for the Peshmerga (Kurdish militia) to try to liberate Kirkuk".

But he warned that many locals were likely to be armed.

"From my grandfather's day, I don't remember our family not having guns in the house," he said.

TURKISH FEARS

While Kurds fear the worst, Turkey has been shaken by scenes of Iraqi Kurds burning the Turkish flag during a recent anti- Turkish protest in Arbil, which organisers say drew up to half a million people, film of which was widely broadcast in Turkey.

As mutual tensions rise, fears of a "war within a war" between Turks and Kurds are also growing in Ankara.

"If the Americans are absent from northern Iraq the danger of clashes between the two becomes greater," one diplomat said. "Sooner or later the U.S. troops will move up into northern Iraq and they will encounter Turkish troops. They would want that to be well co-ordinated and smooth."

Professor Dogu Ergil of Turkey's Tosam research institute said Ankara's traditionally tough line on the Kurds made it hard to be flexible in the current emergency.

"Turkey looks on any development as a threat rather than an opportunity and that has stultified Turkey's position," he said.

If Ankara continues to deny access to U.S. troops, parliament

could pass a separate motion allowing Turkish troops to enter -- or

they could simply follow past procedures and send them in under "hot

pursuit" procedures.

(With additional reporting by Ralph Boulton in Ankara) ![]()

5. - AFP - "Turkey's Erdogan seeks official political

return in by-election":

SIIRT / 7 March 2003 / by Burak Akinci

The head of Turkey's ruling AKP party, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is

set to stage his return to official politics in a parliamentary by-election

here Sunday and then take over the prime minister's post.

The vote comes at a critical juncture for Turkey and the Justice and Development Party (AKP), as Erdogan's election is seen as key to regaining control over the party's rebellious lawmakers who blocked the deployment of 62,000 US troops in Turkey ahead of a possible conflict with Iraq.

A 1998 conviction of "Islamist sedition" in Turkey's strictly-secular political system kept Erdogan from running for parliament last year in elections that swept his AKP to power, but he has been widely seen as the power behind the throne of Prime Minister Abdullah Gul.

Indeed Erdogan has often behaved as a prime-minister-in-waiting, embarking on visits to Europe, the United States and China where he has been given red-carpet treatment. But a series of legal changes pushed through the parliament by AKP has made Erdogan eligible to run in by-elections in the southeastern city of Siirt, where irregularities forced the cancellation of the November vote.

It is seen as a near certainty that Erdogan will win one of the three seats, making him eligible to become prime minister. Gul, a close Erdogan ally, has already indicated he will step down. "The necessary things will be done after the election of our president," Gul was quoted as saying in Thursday's issue of the daily Milliyet.

Erdogan will have his work cut out for him once he gets into office. Despite intense lobbying by the AKP leadership, some the party's deputies refused to endorse the deployment of US troops in Turkey, causing the motion to fail by three votes on March 1.

The rejection was a major embarrassment for AKP leaders, and caused disappointment in Washington, which had been pressing its NATO ally for months to gain a northern route into Iraq in case of a conflict.

It also caused turmoil in Turkey's financial markets as investors fled from stocks and the lira as it appeared that Ankara might lose the six billion dollars (euros) in aid Washington had promised to help cover any damage to the Turkish economy a war might cause.

Analysts say that the government has put off pushing for a new vote on allowing in US troops until Erdogan takes over, and he will be key in putting party recalcitrants back into line.

"By electing one parliamentarian, Siirt will direct the fate of the war," the Milliyet daily rote. Erdogan argues that support for the United States will serve Turkey's interests. In rejecting the motion the parliament also blocked deployment of Turkish troops in northern Iraq.

Ankara fears that the Iraqi Kurds might attempt to break away from Iraq if war erupts, a prospect that could encourage separatism among their restive Turkish cousins.

Staging his political comeback in Siirt will be steeped with irony as it was at a political rally in the city in 1997 that Erdogan's reciting of a poem with religious overtones ended in him being jailed and losing his right to run for parliament. The former mayor of Istanbul -- Turkey's largest city -- served four months of a 10-month prison sentence.

Four parties are contesting the three seats in Siirt. Besides the AKP, the main opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) and two small leftist parties are fielding candidates. But as only the AKP and CHP overcame the threshold of 10 percent of the nationwide vote to get candidates into parliament, their candidates should fill the seats.

The tiny pro-Kurdish Democratic People's Party (DEHAP)

came in first in the November vote with 32 percent, but it failed to

pass the 10 percent nationwide barrier and is boycotting Sunday's vote.

The AKP took 17 percent of the vote in Siirt in the November vote, and

the CHP eight percent. ![]()

6. - Kathimerini - "Cypriot sides confer":

Ahead of summit, Turks back Denktash’s hardline stance

7 February 2003

Prime Minister Costas Simitis met yesterday with Cyprus President

Tassos Papadopoulos to discuss the Cypriot leader’s meeting with

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and Turkish-Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash

in The Hague on Monday.

Simitis and Papadopoulos did not say what policy Greek Cypriots will follow at the meeting. Denktash, after meetings with top Turkish officials in Ankara, said: “It is doubtful we can accept the plan. We need changes to accept it.” Today he will discuss the issue with members of the “parliament” of the breakaway state in northern Cyprus. Tomorrow Papadopoulos will hold talks with the Greek Cypriots’ National Council.

Simitis called on Turkey to press Denktash to accept Annan’s plan for the island’s reunification. “I want to note that despite the constructive stand taken by the Greek-Cypriot side, Mr Denktash, even though he has said he will go to The Hague, has so far remained intransigent. He ignores the dynamic demonstrations which have been held by the Turkish-Cypriot community in support of the solution of the political problem of Cyprus and Cyprus’s accession to the European Union,” Simitis said. “He ignores the desire that exists on the island and in the international community for a solution to the problem,” he added. “Mr Denktash’s position not only leads to the total isolation of the Turkish-Cypriot side but also undermines Turkey’s progress toward EU accession,” Simitis said. “Ankara’s road to Europe passes through the eradication of the dividing lines on Cyprus. That is why I believe the Turkish government ought to contribute decisively to raising the deadlock.”

Denktash received strong backing in Turkey yesterday.

He met with President Ahmet Necdet Sezer, Prime Minister Abdullah Gul,

armed forces chief Hilmi Ozkok and Foreign Minister Yasar Yakis. “In

its present form, the Annan plan is far from meeting the basic concerns

and expectations of Turkish Cypriots,” they said after a four-hour

meeting. “Turkey supports Denktash’s constructive efforts

for peace.” On Wednesday, though, after meeting with Denktash,

ruling party leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan pressed for a solution, saying,

“Both sides must make concessions for agreement to be reached.”

Regarding Denktash, he said: “We do not agree completely on everything...

But our basic aim is, naturally, the happiness and well-being of the

people of northern Cyprus.” ![]()